MALI

K7

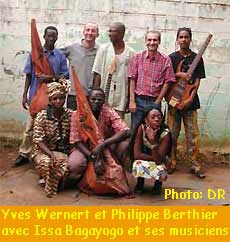

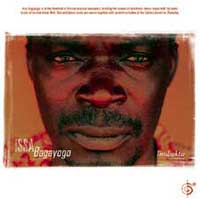

African Music's Dream Factory Paris, 17 January 2002 - After making his name as a trendy punk-rock record store owner in Lyons in the early 80s, Philippe Berthier flew out to Mali to begin a new life in Bamako. Now, eighteen years later, the enterprising Frenchman runs MaliK7, the country's sole cassette production company. He also co-owns a recording studio with world music star Ali Farka Touré. Working in close collaboration with French arranger Yves Wernert (a former bass-player from Nancy), Berthier has helped launch the careers of a number of leading "Afro-electro" stars such as Issa Bagayogo - better known as "Techno Issa" in Mali!  Following

Berthier's instructions, we make our way up a dirt track, turn "just

past the tarmac and the Shell service station" and finally come

upon a small blue-and-yellow sign pointing the way to MaliK7, the country's

one and only cassette factory. Entering the premises we find a small

and modest structure - no sign of spanking new offices, piles of stock

or stacks of promotional gifts. Just one ordinary-looking building housing

the cassette pressing machines, the sleeve-printer, offices, the in-house

shop and the reception area. Welcome to MaliK7, the record company responsible

for catapulting Ali Farka Touré, Lobi Traoré and Neba Solo to fame! Following

Berthier's instructions, we make our way up a dirt track, turn "just

past the tarmac and the Shell service station" and finally come

upon a small blue-and-yellow sign pointing the way to MaliK7, the country's

one and only cassette factory. Entering the premises we find a small

and modest structure - no sign of spanking new offices, piles of stock

or stacks of promotional gifts. Just one ordinary-looking building housing

the cassette pressing machines, the sleeve-printer, offices, the in-house

shop and the reception area. Welcome to MaliK7, the record company responsible

for catapulting Ali Farka Touré, Lobi Traoré and Neba Solo to fame!

Listening to a battered old radio set crackle out the latest Alpha Blondy hit, MaliK7's receptionist sits beneath an Oumou Sangare poster, singing along as she cuts out cassette sleeves from a long roll. With MaliK7's albums retailing at 850 CFA (8.5 francs or 1.30 euros) - prices haven't changed since 1992 despite the deflation of the CFA and the soaring prices of raw materials - the company's fifteen employees are used to doing several jobs at once! Meanwhile, a catchy mix of Afro-electro groove drifts from the studio across the road, where Ali Farka Touré's guitarist, Moussa Koné, is rehearsing with Issa Bagayogo. When Philippe Berthier set up Studio Bogolan in 1988 it was the first multi-track recording studio in Mali, but over the last fifteen years the French entrepreneur has seen huge changes in the country's music industry. These days Mali boasts several recording studios, a host of local and foreign producers and a music copyright office affiliated to the French organisation SACEM. However, there's still no sign of any state subsidies for musical production! While MaliK7 only produces six or seven albums a year, the company assures the distribution of local Mali talent (some twenty new albums a month) as well as international stars such as Janet Jackson, Whitney Houston and Mariah Carey. RFI/Musique met up with MaliK7's director, Philippe Berthier, and stepped behind the scenes at the tiny 15-employee company which presses the dreams of thousands of Malian music fans:  RFI/Musique:

So, Philippe, let's begin by asking how someone born and brought up

in Lyon ends up running a cassette production company in Mali? RFI/Musique:

So, Philippe, let's begin by asking how someone born and brought up

in Lyon ends up running a cassette production company in Mali?Philippe Berthier: Well, I came to Mali completely by chance in 1982 to see friends of mine out here. I had a brilliant time and when I went back to Lyons, where I had my own record shops specialising in punk and rock, I basically got the blues. In fact, I missed Africa so much I decided I wanted to come out and live here. So I drove across Europe and North Africa and, after spending three months in Algeria, arrived in Bamako in January 1985. I started off working for a big French company, but I already had this idea at the back of my mind that I wanted to set up my own structure. Anyway, after that I went out to work in Zaire for a while, then I flew back to France to buy all the necessary recording equipment to set up my own studio. By the end of '88, I'd opened Mali's first multi-track recording studio in Bamako. Before I created my studio, local musicians had only been able to work in a double-track studio belonging to ORTM (Mali's national radio station). Once I'd set up the studio I realised we also needed to create a company to oversee the production of cassettes. The only thing you could get your hands on on the record market in Mali were pirate cassettes from abroad. So one year later I went on to set up "Ou Bien Productions". And in 1992 we struck a deal with EMI, which already had subsidiaries in Nigeria and the Ivory Coast… Anyway, to cut a long story short, EMI totally pulled out of Africa in 1995 (only keeping a base in South Africa). And it was then that I went into business with Ali Farka Touré. He'd just won a Grammy Award and we set up "MaliK7" together. Your

biggest problem to date has been cassette 'pirating'. In fact, I believe

at one point you almost closed down because of it? Have

you noticed any major changes on the Malian music scene since you arrived?

Is

it easy to promote your artists in Mali? What

are your best-selling acts in Mali right now? Where

do you sell your cassettes? Interview:

Elodie Maillot |

||

With

such a hotbed of musical talent at your disposal, how do you go about

deciding which artists you want to produce?

With

such a hotbed of musical talent at your disposal, how do you go about

deciding which artists you want to produce?