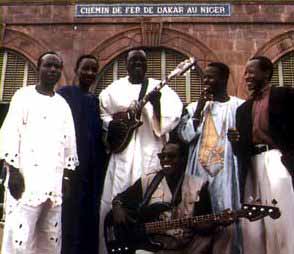

|  Super

Rail Band

de Bamako Salif Keita et Mory

Kanté firent leurs premiers pas au sein de cet orchestre mythique.

Inédites et récentes, les chansons originales ou puisées aux traditions,

célèbrent le courage, l'honnêteté, le respect d'autrui, … Super

Rail Band

de Bamako Salif Keita et Mory

Kanté firent leurs premiers pas au sein de cet orchestre mythique.

Inédites et récentes, les chansons originales ou puisées aux traditions,

célèbrent le courage, l'honnêteté, le respect d'autrui, …

Voix haut

perchées et mélodies ondoyantes, cuivres colorés et guitares ébouriffantes

font carburer la locomotive d'or de Bamako, qui bourlingue du blues

de la savane au rock mandingue urbain.

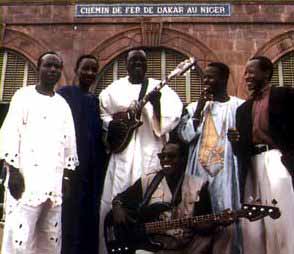

Au Mali, où la musique traditionnelle a toujours fait preuve d'une vitalité

extraordinaire, il fallut attendre 1970 pour que  naisse

le premier groupe de "folklore modernisé" comme on appelait alors la

musique africaine électrifiée. Ce groupe, le Super

Rail Band du Buffet-hôtel de la gare de Bamako, sera à la musique

mandingue moderne ce que furent E. T. Mensah

au high-life (Ghana), Mahlathini au mbaqanga

(Afrique du Sud) ou I.K. Dairo à la juju

music (Nigeria). naisse

le premier groupe de "folklore modernisé" comme on appelait alors la

musique africaine électrifiée. Ce groupe, le Super

Rail Band du Buffet-hôtel de la gare de Bamako, sera à la musique

mandingue moderne ce que furent E. T. Mensah

au high-life (Ghana), Mahlathini au mbaqanga

(Afrique du Sud) ou I.K. Dairo à la juju

music (Nigeria).

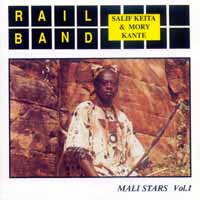

Ses chanteurs successifs - dont l'Occident connaît surtout les deux

premiers, Salif Keita et Mory

Kanté - seront les superstars incontestées de la scène malienne

jusqu'à l'avènement de la musique du Wassoulou dans les années 90.

Depuis la soirée mémorable du premier concert du Rail

Band en mars 1970, où Salif

Keita chanta du fond de la scène et la tête couverte d'une serviette

de bain tant il avait honte de s'abaisser au métier de griot,

bien de l'eau a passé sous les ponts du Niger, et le groupe a connu

ses moments de doute. Ainsi au milieu des années 70 enregistrait-il

à Lagos deux albums de rumba, pour tenter d'épouser la mode zaïroise

qui balayait l'Afrique. Puis vint la mode des "musiques du monde" en

Occident, et le Rail Band revint tout doucement

au beau style mandingue de ses débuts, le seul dans lequel il se savait

inégalable.

Mais après

plus de 25 ans de carrière, un groupe a besoin d'évoluer. C'est au niveau

du son qu'il pouvait le faire, sans trahir la pureté de son style. Ce

nouvel album garde l'ample respiration héritée des griots,

les mélodies superbes, les guitares acides en contrepoint de cuivres

berceurs, mais le mix est moderne. Notre écoute a changé, et le présent

enregistrement réalisé avec le concours de Xavier

Jouvelet (percussionniste de Ray Lema

et Papa Wemba) rend compte de cette évolution.

L'accompagnement de Jean-Philippe Rykiel,

"seul blanc à sonner comme un africain" selon Salif

Keita, donne à la musique une profondeur inédite. Les cuivres, augmentés

de musiciens parisiens, suivent scrupuleusement les riffs originaux,

tandis qu'à la guitare solo Djelimady

Tounkara fait, comme toujours, des merveilles de précision liquide.

Ces deux albums enregistrés sur Indigo, le premier éponyme et le second

Mansa, viennent couronner 25 années d'une carrière formidable, et prouver

la longévité d'un des plus grands groupes du continent africain.

|

|  Salif

Keita

and Mory Kanté took their first

steps in music with this mythical band. All the songs are recent and

unprecedented, and whether they are original or inspired by tradition,

they are a celebration to courage, honesty, respect for others… Salif

Keita

and Mory Kanté took their first

steps in music with this mythical band. All the songs are recent and

unprecedented, and whether they are original or inspired by tradition,

they are a celebration to courage, honesty, respect for others…

High-pitched

voices and undulating melodies, colourful brass and unbelievable guitars

are the fuel for Bamako's golden locomotive, which thunders from savannah

Blues to urban Manding rock.

In Mali, where traditional music has always been of an extraordinary

vitality, the birth of the first "modernised folk" band, as African

electric music was then called, was not witnessed until 1970.

This group, the Super Rail Band of Bamako,

was to become to modern Manding music what E.

T. Mensah was to High-Life (Ghana), what Mahlathini

was to Mbaqanga (South Africa) and what I. K.

Dairo was to Juju Music (Nigeria). The band's successive singers

- of whom the first two, Salif Keita

and Mory Kante, are best known in

the West - were to become the uncontested superstars of the Malian musical

scene right up until the arrival of Wassoulou music in the nineties.

However,

at lot has happened since the memorable night of the Rail

Band's first concert in March 1970, when Salif

Keita sang from the back of the stage, his head covered by a bath

towel, so great was his shame in lowering himself to the level of Griot,

and the group has had its moments of doubt. They thus recorded two rumba

albums in the mid-seventies in an attempt to join the Zairian trend

that was sweeping across Africa at the time. Then came the craze for

"World Music" in the West and the Rail Band

gently returned to their original Manding style, knowing that they were

unequalled in this style. But after a career spanning more than 25 years,

a group needs to evolve. It was with their sound that they could do

so, without betraying the purity of their style. However,

at lot has happened since the memorable night of the Rail

Band's first concert in March 1970, when Salif

Keita sang from the back of the stage, his head covered by a bath

towel, so great was his shame in lowering himself to the level of Griot,

and the group has had its moments of doubt. They thus recorded two rumba

albums in the mid-seventies in an attempt to join the Zairian trend

that was sweeping across Africa at the time. Then came the craze for

"World Music" in the West and the Rail Band

gently returned to their original Manding style, knowing that they were

unequalled in this style. But after a career spanning more than 25 years,

a group needs to evolve. It was with their sound that they could do

so, without betraying the purity of their style.

Their latest

album preserves the ample breathing inherited from the Griots,

the superb melodies, the acid guitars which counterbalance the soothing

brass, but the mix is modern.

Our way of listening has changed and this recording, produced with the

assistance of Xavier Jouvelet (percussionist

for Ray Lema and Papa

Wemba) takes this change into account. Jean-Philippe

Rykiel's accompaniment, "the only white to sound like an

African" according to Salif Keita,

adds a new depth to the music. The brass section, augmented by a number

of Parisian musicians, scrupulously follows the original riffs, while

Djelimady Tounkara delivers,

as ever, marvellously precise and fluid guitar solos.

These

two albums on Indigo, the first one eponymous, the second Mansa, crown

a remarkable twenty-five year career and attest to the longevity of

one of Africa's greatest groups. |

Super

Rail Band

de Bamako

Super

Rail Band

de Bamako  naisse

le premier groupe de "folklore modernisé" comme on appelait alors la

musique africaine électrifiée. Ce groupe, le Super

Rail Band du Buffet-hôtel de la gare de Bamako, sera à la musique

mandingue moderne ce que furent E. T. Mensah

au high-life (Ghana), Mahlathini au mbaqanga

(Afrique du Sud) ou I.K. Dairo à la juju

music (Nigeria).

naisse

le premier groupe de "folklore modernisé" comme on appelait alors la

musique africaine électrifiée. Ce groupe, le Super

Rail Band du Buffet-hôtel de la gare de Bamako, sera à la musique

mandingue moderne ce que furent E. T. Mensah

au high-life (Ghana), Mahlathini au mbaqanga

(Afrique du Sud) ou I.K. Dairo à la juju

music (Nigeria).