|  "Le

bonheur n'est pas pour demain, il n'est pas hypothétique, il

commence ici et maintenant. Ne nous laissons pas dominer par la violence,

l'égoïsme, le désespoir. Ne sacrifions pas au culte

du pessimisme. Relevons-nous. La nature nous adonné des cadeaux

extraordinaires. Rien n'est encore joué pour notre continent,

rien n'est encore perdu. Profitons enfin de ses merveilles. Intelligemment,

à notre façon, à notre rythme, en hommes responsables

et fiers de leur héritage. Bâtissons la terre de nos enfants

et arrêtons de nous apitoyer sur nous-mêmes. L'afrique,

c'est aussi la joie de vivren l'optimisme, la beauté, l'élégance,

la grâce, la poésie, la douceur, le soleil, la nature.

Soyons heureux d'en être les fils et luttons ensemble pour construire

notre bonheur. " "Le

bonheur n'est pas pour demain, il n'est pas hypothétique, il

commence ici et maintenant. Ne nous laissons pas dominer par la violence,

l'égoïsme, le désespoir. Ne sacrifions pas au culte

du pessimisme. Relevons-nous. La nature nous adonné des cadeaux

extraordinaires. Rien n'est encore joué pour notre continent,

rien n'est encore perdu. Profitons enfin de ses merveilles. Intelligemment,

à notre façon, à notre rythme, en hommes responsables

et fiers de leur héritage. Bâtissons la terre de nos enfants

et arrêtons de nous apitoyer sur nous-mêmes. L'afrique,

c'est aussi la joie de vivren l'optimisme, la beauté, l'élégance,

la grâce, la poésie, la douceur, le soleil, la nature.

Soyons heureux d'en être les fils et luttons ensemble pour construire

notre bonheur. "

Salif

Keita,

décembre 2001

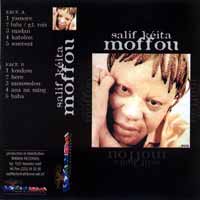

Moffou,

c'est à la fois le titre du dernier album de Salif

Keïta et le nom du club que le chanteur vient d'ouvrir à

Bamako pour y promouvoir la scène musicale ouest-africaine. Dans

l'un comme dans l'autre cas, le choix de ce patronyme n'est pas gratuit,

il exprime un réel désir de retour aux racines, au continent

Noir, au Mali, au pays des Bambara, Malinké et Soninké,

à ses cultures, modes de vie, rites et traditions. De quoi contrarier

les détracteurs de celui que l'on a surnommé le "Caruso

africain", qui l'accusent de s'être beaucoup trop éloigné

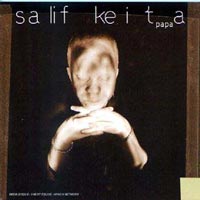

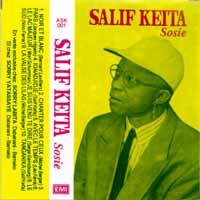

de ses origines. Certes, Sosie, paru en 1997, était entièrement

consacré à la chanson française, et Papa, cru 1999

enregistré pour partie à New York, produit par le guitariste

funk-rock Vernon Reid, ne lésinait pas sur l'électronique

et les rythmes urbains. Mais à l'instar de Folon (1995), pétri

de tradition mandingue, Moffou, cédé entièrement

acoustique, est une œuvre d'inspiration cent pour cent africaine.

Influences soul et pop mises en berne, Salif Keïta,

voix céleste d'une clarté et d'une vigueur exceptionnelles,

livre là l'un de ses enregistrements les plus frais, enivrants

et authentiques.

Peut-être

bien le sommet d'une carrière qui commence trente-quatre ans

plus tôt, en 1968, lorsque Salif,

20 piges et des poussières, quitte les rives du fleuve Niger,

les champs et le domicile familiaux pour tenter sa chance dans la capitale,

Bamako. Plutôt qu'un départ : une fuite, une rupture. Parce

que l'enfance et l'adolescence de Salifou Keïta,

venu au monde le 25 août 1949 dans le village de Djoliba (c'est

le premier nom du Niger), au cœur du Mali, n'ont pas été

une véritable partie de plaisir. Peut-être

bien le sommet d'une carrière qui commence trente-quatre ans

plus tôt, en 1968, lorsque Salif,

20 piges et des poussières, quitte les rives du fleuve Niger,

les champs et le domicile familiaux pour tenter sa chance dans la capitale,

Bamako. Plutôt qu'un départ : une fuite, une rupture. Parce

que l'enfance et l'adolescence de Salifou Keïta,

venu au monde le 25 août 1949 dans le village de Djoliba (c'est

le premier nom du Niger), au cœur du Mali, n'ont pas été

une véritable partie de plaisir.

Caprice du sort, mauvais coup du destin, il naît albinos. Noir

à la peau blanche : une malédiction dans cette partie

du monde ! Les croyances - pour ne pas dire superstitions autochtones

leur attribuent des pouvoirs néfastes, leur différence

physique entraîne moqueries, mauvais traitements et mise à

l'index, les rayons du soleil ô combien brûlants en cette

région - sont une véritable torture et leur vue est considérablement

altérée. Le bébé est caché, renié,

isolé. Son père mettra des années avant de consentir

à lui adresser la parole. Le gamin grandit en solitaire, se plonge

avec délectation dans la lecture, les études et se prend

de passion pour le chant des griots,

poètes itinérants qui vont ci et là conter les

épopées royales, colporter les odyssées familiales

et transmettent les traditions orales de génération en

génération. Et c'est dans la campagne, où il passe

une partie de ses journées à vociférer contre les

alouettes, martinets, patas et babouins qui fondent sur les plantations

de maïs paternelles, qu'il se façonne cette voix aussi étonnante

que saisissante, unique et immédiatement identifiable.

Seulement voilà, chez les Keïta,

fiers agriculteurs de père en fils, on se revendique de noble

extraction, descendants directs du valeureux et tant redouté

Sounjata, petit prince chétif et paralytique qui accomplit la

formidable prouesse de fédérer un grand nombre de clans

ennemis et forma au début du XIIIe siècle le puissant

Empire du Mali (dont les frontières englobaient alors le Sénégal,

la Guinée, le Burkina et une partie de la Mauritanie, de la Côte

d'Ivoire et du Niger actuels).

Un aristocrate ne chante pas ! L'entourage du jeune Salif,

là-dessus, s'avère intraitable. La musique reste l'affaire

exclusive de la caste des griots. Choisir

leur voie, c'est transgresser des règles ancestrales et s'exclure

de fait de la communauté. Une seule issue : partir.

Bamako,

fin des années soixante. La voix de Salif

Keïta, petit à petit, séduit les musiciens

de la métropole. A commencer par le saxophoniste Tidiane

Koné, leader du Rail Band

de Bamako qui fait les beaux soirs de l'Hôtel de la Gare (chaque

hôtel de la capitale possède son orchestre). Bamako,

fin des années soixante. La voix de Salif

Keïta, petit à petit, séduit les musiciens

de la métropole. A commencer par le saxophoniste Tidiane

Koné, leader du Rail Band

de Bamako qui fait les beaux soirs de l'Hôtel de la Gare (chaque

hôtel de la capitale possède son orchestre).

Impressionné par ses capacités vocales proprement hallucinantes,

Koné embauche le jeune homme. Lequel

devient la véritable vedette de l'ensemble et le conduit rapidement

au succès.

En 1973,

cédant sa place à un jeune chanteur guinéen encore

inconnu - Mory Kanté -, Salif

rejoint Les Ambassadeurs, autre formation

de danse menée par le guitariste et chanteur Kanté

Manfila. Etabli au Motel de Bamako, endroit essentiellement fréquenté

par des Occidentaux, l'orchestre propose un répertoire éclectique

et élargi, mordant sérieusement sur la pop anglo-saxonne,

la chanson française et les rythmes afro-cubains. Premières

tournées dans toute l'Afrique de l'Ouest puis expatriation pour

la Côte d'Ivoire, en l'occurrence sa capitale, Abidjan, ville

techniquement et commercialement beaucoup mieux équipée

que Bamako. En 1978, Salif et les siens

y enregistrent Mandjou, énorme réussite commerciale notamment

due au titre du même nom. C'est là le vrai décollage

de sa carrière internationale.

La griffe,

le son et le style Keïta sont déjà

présents : orgue, claviers, guitares et saxophones se mêlent

aux percussions et cordes traditionnelles, bribes de jazz, de rock,

de funk et d'afro-beat redessinent les contours de rythmes et mélopées

ancestraux.

Décembre

1980 : Salif et Kanté

traversent l'Atlantique et se posent pour trois mois à New York.

Le temps de mettre en boîte les albums Primpin et Toukan, qui

susciteront le même enthousiasme que Mandjou. Mais Salif,

déjà, a l'esprit ailleurs. Il rêve de Paris.

En France, le mouvement afro est en plein essor, entraîné

par des personnalités telles que Pierre

Akendengué, Manu Dibango

ou Ray Lema. Au printemps 1984, notre homme

triomphe au Festival des musiques métisses d'Angoulême.

Le public français l'a conquis, c'est décidé, le

Malien abandonne Abidjan pour venir planter sa tente dans l'Hexagone.

Il se coule humblement et discrètement dans la communauté

malienne de Montreuil, en proche banlieue parisienne.

1985 : il répond à l'invitation de

Manu Dibango et participe à l'enregistrement du titre

Tam Tam pour l'Afrique dont les royalties sont entièrement reversés

au profit de l'Ethiopie, où la famine n'a jamais été

aussi meurtrière.

En 1987,

Salif retrouve les studios pour la première

fois en six ans. Produit par le Sénégalais Ibrahim Sylla,

sur des arrangements de François Bréant

et Jean-Philippe Rykiel, il publie Soro,

manière de blues mandingue chanté en malinké (langue

la plus importante du groupe Mandé). Un disque d'une pureté

étincelante, son premier vrai chef d'oeuvre. Un carton ! En octobre,

invité en Angleterre pour un concert organisé à

l'occasion des 70 ans de Nelson Mandela, il se retrouve entouré

de stars consacrées - Youssou N'Dour,

Ray Lema - et se voit intégré

au cercle restreint des maîtres de la " World music".

S'ensuivront

quantité de tournées aux quatre coins du globe. Ponctuées

par les albums Ko-Yan (1988) et Amen (1991), placé sous la direction

artistique de Joe Zawinul (parmi les invités

: Wayne Shorter, Carlos

Santana et son compatriote le claviériste Cheick

Tidiane Seck), ainsi que plusieurs séries de concerts

en compagnie du Syndicate du même

Zawinul, héros de la fusion que

Salif admire depuis les premiers albums

de Weather Report, au début des

années 70 : "Joe, je le rejoins quand il veut. C'est

un frère, un immense créateur ! " Et puis encore

Folon (1995), produit par le Béninois Wally

Badarou (Grace Jones, Peter

Tosh, Joe Cocker) et arrangé

une nouvelle fois par Rykiel (sur la pochette

: Nantenin, la nièce elle aussi albinos de l'artiste), troisième

pure merveille du Malien, le francophile Sosie (1997) et le funky Papa

(1999), tous deux cités plus haut.

A

partir de 1997, Salif Keïta retourne

de plus en plus fréquemment au Mali. A

partir de 1997, Salif Keïta retourne

de plus en plus fréquemment au Mali.

Conservant un pied-à-terre à Montreuil, où vivent

une bonne partie de ses (nombreux) enfants, il ouvre un studio à

Bamako, commence à y produire de jeunes artistes (Fantani

Touré, Rokia Traoré)

et se consacre de plus en plus à la fondation "SOS Albinos",

qu'il a créée en 1990 pour conseiller, orienter et aider

ses frères et sœurs d'infortune.

Panafricain dans l'âme, antiraciste convaincu, militant de la

paix, grand laudateur de Nelson Mandela, artiste d'une générosité

peu commune qui s'est toujours ingénié à dresser

de multiples passerelles entre l'Afrique et le reste du monde, il aborde

aujourd'hui un nouveau tournant de son existence. Celui de la maturité

(la sagesse ?). Laquelle le pousse à s'investir plus avant dans

la destinée de son pays, encourager le retour des émigrés,

protéger et promouvoir les artistes locaux et œuvrer pour

que la musique africaine s'émancipe et ne se conçoive

plus essentiellement en Europe ou aux Etats-Unis mais sur sa terre d'origine.

A l'heure

où le continent Noir semble assailli par les maux les plus infects

guerres tribales, ethniques et transnationales, exploitation éhontée

des ressources naturelles par les multinationales, politique vérolée

souvent liée aux luttes intestines pour le contrôle des

gisements - or, pétrole, cuivre, diamants -, pollution, corruption

des élites, surendettement, analphabétisme, misère,

famine, maladies dévastatrices, extension affolante du sida,

catastrophes naturelles à la pelle, massacre des espèces

protégées, destruction de la forêt), Salif

Keïta, lui, refuse obstinément de s'inscrire dans

le fatalisme, de sombrer dans le défaitisme et de s'abandonner

à l'apitoiement : "Le bonheur n'est pas pour demain,

il n'est pas hypothétique, il commence ici et maintenant. Ne

nous laissons pas dominer par la violence, l'égoïsme, le

désespoir. Ne sacrifions pas au culte du pessimisme. Relevons-nous.

La nature nous a donné des cadeaux extraordinaires. Rien n'est

encore joué pour notre continent, rien n'est encore perdu. Profitons

enfin de ses merveilles. Intelligemment, à notre façon,

à notre rythme, en hommes responsables et fiers de leur héritage.

Bâtissons la terre de nos enfants et arrêtons de nous apitoyer

sur nous-mêmes. L¹Afrique, c'est aussi la joie de vivre,

l'optimisme, la beauté, l'élégance, la grâce,

la poésie, la douceur, le soleil, la nature. Soyons heureux d'en

être les fils et luttons ensemble pour construire notre bonheur".

Discours

que traduisent les textes de Moffou, chantés en malinké

et en bambara, qui en appellent à la joie, à l'amour et

évoquent les douceurs et bienfaits de la vie. Joli cocktail d'ambiances

que cette galette aux couleurs chatoyantes, à l'énergie

hautement communicative et, surtout, au très fort pouvoir émotionnel.

Thèmes

dansants, chaloupés et charnels, "des rumbas sauvages"

selon leur signataire (Baba, Madan, Moussolou, Koukou), côtoient

chansons douces et ballades (Here, Souvent ou l'incomparable Ana na

ming, merveille d'épure écrite alors que Salif

Keïta, séjournant seul sur une petite île,

rêvait d'une compagne imaginaire).

Une cohorte d'excellents musiciens participent à l'opération.

Au rang desquels le guitar-hero guinéen Djelly

Moussa Kouyaté (dont le prochain album, Sebe Alaye, est

attendu avec impatience) et l'incontournable Kante

Manfila (guitare acoustique), tous deux compagnons de longue

date de Salif. Et puis la voix de Cesaria

Evora dans Yamore, l'accordéon de Benoît

Urbain, l'harmonica, le marimba et les steel-drums d'Arnaud

Devos, les percussions du terrassant Mino

Cinelu, les flûtes de David Aubaile

et, côté instruments traditionnels, les calebasses,

tams, congas africaines et djembés

de Mamadou Koné, Adama

Kouyaté, Souleymane Doumbia

et Drissa Bakayoko, les luths de Jean-Louis

Solans et Mehdi Haddad (Ekova),

les n'goni (petites guitares)

de Sayon Sissoko et Harouna

Samaké. Le tout produit par Jean

Lamoot (Noir Désir, Alain

Bashung, Brigitte Fontaine, Mano

Solo…).

Casting de rêve pour un album rêvé dont on n'a pas

fini de parler.

|

|  "Happiness

is not for tomorrow, it’s not hypothetical, and it begins here

and right now. Let’s fight against violence, selfishness and desperation.

Do no sacrifice to the cult of pessimism. Stand up. Nature gave us extraordinary

gifts. Nothing is done on our continent yet, nothing is lost. Let’s

take advantage from these wonders, cleverly, in our manner, at our rhythm,

like men responsible and proud of their inheritance. Let’s built

something for our children and let’s stop feeling pity for ourselves.

Africa is also the pleasure to be alive, optimism, beauty, elegance,

grace, poetry, sweetness, sun, nature. Let’s be happy to be the

sons of it and let’s struggle together to built our happiness". "Happiness

is not for tomorrow, it’s not hypothetical, and it begins here

and right now. Let’s fight against violence, selfishness and desperation.

Do no sacrifice to the cult of pessimism. Stand up. Nature gave us extraordinary

gifts. Nothing is done on our continent yet, nothing is lost. Let’s

take advantage from these wonders, cleverly, in our manner, at our rhythm,

like men responsible and proud of their inheritance. Let’s built

something for our children and let’s stop feeling pity for ourselves.

Africa is also the pleasure to be alive, optimism, beauty, elegance,

grace, poetry, sweetness, sun, nature. Let’s be happy to be the

sons of it and let’s struggle together to built our happiness".

Salif

Keita,

December 2001

Moffou

is the name of the last album of Salif Keita

and also the name of the club he has opened in Bamako to promote the

West African musical scene. This name express a real desire to return

to the roots, to the black continent, to Mali, to the country of the

Bambara, Malinke and Soninke, to cultures, way s of life, rites and

traditions. It comes as an answer to those who accused him to have gone

too far from his origins.

Sure, “Sosie”, released in 1997, was totally consecrated

to French songs and “Papa”, released in 1999, recorded in

part in New York and produced by the funk rock guitar player Vernon

Reid, was full of electronic and urban rhythms. Like “Folon”

(1995), full of Mandingo tradition, “Moffou” is totally

acoustic and also full of tradition. Salif Keïta

with his celestial clear and vigorous voice gives here a cool and authentic

recording.

Maybe

the top of a career begun 34 years earlier when Salif,

20 years old left the banks of the river Niger and the familial fields

and house to try his chance in Bamako. More than a living, it was a

flight, a rupture. Salifou Keïta was

born on August 25th, 1949 in the village Djoliba (first name of the

river Niger) in the center of Mali and his childhood and adolescence

wasn’t pleasure at all. Maybe

the top of a career begun 34 years earlier when Salif,

20 years old left the banks of the river Niger and the familial fields

and house to try his chance in Bamako. More than a living, it was a

flight, a rupture. Salifou Keïta was

born on August 25th, 1949 in the village Djoliba (first name of the

river Niger) in the center of Mali and his childhood and adolescence

wasn’t pleasure at all.

Unfortunately, he is an albino. Black with white skin: a very bad curse

in this part of the world! The aboriginal superstition attribute to

it fatal powers, their difference leads to mockery, bad treatments and

rejection; the sun, which is particularly burning in this region, is

a real torture for their skin and eyes, so their vision is generally

very spoilt. The baby was hidden, repudiated, isolated. His father spent

several before accepting to talk to him. The child grew up alone, dipped

himself with delight into reading, studying and had a real passion for

the songs of the griots (itinerant poets

who go every where to relate the royal epics, the familial saga and

to transmit the oral traditions from generation from generation. So

it’s in the country where he spent most of his time shouting out

to larks, martlets and Baboons which swoop down on the paternal corn

plantation that he fashioned this so astonishing and gripping voice,

unique and immediately recognizable.

But, by

the Keita, proud farmers from father to son, they claim to be from noble

family, directs descendants of the brave and also feared Sunjata, small

wretched prince unable to move with his legs who accomplished the unbelievable

prowess to federate several enemies and formed at the beginning of the

XIII century the powerful empire of Mali (the frontiers included at

that time the present Senegal, Guinea, Burkina and part of Mauritania,

Ivory Coast and Niger). An aristocrat does not sing! The family of Salif

was unmanageable on this point. Music is exclusively for the griots.

To choose this way is to transgress the ancestral rules and to exclude

oneself from the community. Only one issue: leaving.

Bamako,

end of the sixty’s. Salif Keïta’s

voice seduces slowly the musicians of the metropolis. The first was

the saxophonist Tidiane Koné, leader

of the band Rail Band of Bamako.

Impressed by his incredible vocal capacities, Koné

engaged the young man who became the real star of the band and led it

to success.

In 1973,

giving up his place to a young Guinean singer still unknown - Mory

Kante -, Salif rejoin the band “Les

Ambassadeurs”, another dancing band leaded by the guitar

player and singer Kanté Manfila.

Established at the “Bamako Motel”, place essentially frequented

by Occidentals, the orchestra proposed an electrical and enlarged repertoire,

with Anglo-Saxon pop, French songs and afro Cuban rhythms. First tours

in all West Africa then expatriation in Abidjan which is technically

and commercially much better equipped than Bamako.

In 1978, Salif and his band recorded “Mandjou”

there; it was a huge success commercially speaking especially because

of the song with the same title. Then began his international career.

The label,

sound and style Keïta are presents:

organ, keyboard, guitar and saxophones join the percussions and traditional

strings and some jazz, rock and afro beat redraw the ancestral rhythms

and melodies.

December 1980: Salif and Kanté

arrive in New York for three months; just the time to record the albums

“Primpin” and “Toukan” which will meet the same

success as “Mandjou”. But Salif’s

mind is already elsewhere. He dreams of Paris. In France, the afro movement

is booming, leaded by personalities such as Pierre

Akendengué, Manu Dibango

or Ray Lema. During the spring 1984, our

man had a huge triumph at the “Festival des musiques métisses

d'Angoulême.” The French public conquered him so he decided

to leave Ivory Coast to move in France. He slipped humbly and discreetly

into the Malian community of Montreuil (Parisian suburbs).

1985: Manu Dibango invited him for the

recording of “Tam Tam pour l'Afrique (tam tam for Africa)”

which royalties were totally reversed to Ethiopia where famine was ruder

then ever.

In 1987,

Salif returns in the studios for the first

time since six years. Produced by the Senegalese Ibrahim Sylla, on the

arrangements of François Bréant

and Jean-Philippe Rykiel, he published

“Soro”, kind of Mandingo blues sung in Malinke (most important

language of the Mande); a sparkling pure album, his first masterpiece.

In October, as invited in England for the 70 years old celebration of

Nelson Mandela, he found himself surrounded by consecrated star such

as Youssou N'Dour, Ray

Lema and is integrated into the restricted circle of the masters

of “World music”.

Thereafter

came a lot of tours around the world. These tours were punctuated by

the albums Ko-Yan (1988) and Amen (1991), placed under the artistic

direction of Joe Zawinul (among the guest:

Wayne Shorter, Carlos

Santana and his compatriot the keyboard player Cheick

Tidiane Seck) and by several concerts made with the syndicate

of the same Zawinul, hero of fusion whom

Salif admired since the first albums of

Weather Report at the beginning of the

seventy’s: “I can rejoin Joe any time I like. He’s

like my brother, a huge creator!” and then Folon (1995),

produced by the Beninese Wally Badarou

(Grace Jones, Peter

Tosh, Joe Cocker) and arranged by

Rykiel (on the album appears Nantenin,

the albino niece of the artist), third pure wonder of the Malian, the

Francophile Sosie (1997) and the funky Papa (1999), both quoted above. Thereafter

came a lot of tours around the world. These tours were punctuated by

the albums Ko-Yan (1988) and Amen (1991), placed under the artistic

direction of Joe Zawinul (among the guest:

Wayne Shorter, Carlos

Santana and his compatriot the keyboard player Cheick

Tidiane Seck) and by several concerts made with the syndicate

of the same Zawinul, hero of fusion whom

Salif admired since the first albums of

Weather Report at the beginning of the

seventy’s: “I can rejoin Joe any time I like. He’s

like my brother, a huge creator!” and then Folon (1995),

produced by the Beninese Wally Badarou

(Grace Jones, Peter

Tosh, Joe Cocker) and arranged by

Rykiel (on the album appears Nantenin,

the albino niece of the artist), third pure wonder of the Malian, the

Francophile Sosie (1997) and the funky Papa (1999), both quoted above.

From 1997, Salif Keïta returns more

frequently in Mali. He keeps a pied-à-terre in Montreuil where

a big part of his numerous children live and open a studio in Bamako

and produces young artists (Fantani Touré,

Rokia Traoré) and consecrates

more and more to the foundation “SOS Albinos” that he created

in 1990 in order to advise, orientate and help his brothers and sisters

of misfortune.

Panafrican

in soul, convinced antiracist, militant of peace, great admirer of Nelson

Mandela, Salif Keita is also a generous

artist who has always done his best to create a footbridge between Africa

and the rest of the world who approach today a new turning point of

his life: the one of maturity. This push him to invest more in the development

of his country, to encourage the expatriates, to protect and promote

the local artists and to act in order to make the African music emancipate

and be produced on the original land and not only in Europe and united

states.

At the time when the black continent is assailed by the most filthy

evil – tribal, ethnical and international wars, shameless exploitations

of the natural resources by the multinational enterprises, rotten politics

linked to intern struggle for the control of gold, hydrocarbure,  copper,

diamonds deposits , pollution, corruption of the leaders, indebtedness,

illiteracy, misery, famine, devastating diseases, alarming extension

of AIDS, natural disasters, slaughtering of protected species, destruction

of the forests, Salif Keïta refuses

to be fatalist and defeatist and feel pity. “Happiness is

not for tomorrow, it’s not hypothetical, and it begins here and

right now. Let’s fight against violence, selfishness and desperation.

Do no sacrifice to the cult of pessimism. Stand up. Nature gave us extraordinary

gifts. Nothing is done on our continent yet, nothing is lost. Let’s

take advantage from these wonders, cleverly, in our manner, at our rhythm,

like men responsible and proud of their inheritance. Let’s built

something for our children and let’s stop feeling pity for ourselves.

Africa is also the pleasure to be alive, optimism, beauty, elegance,

grace, poetry, sweetness, sun, nature. Let’s be happy to be the

sons of it and let’s struggle together to built our happiness.” copper,

diamonds deposits , pollution, corruption of the leaders, indebtedness,

illiteracy, misery, famine, devastating diseases, alarming extension

of AIDS, natural disasters, slaughtering of protected species, destruction

of the forests, Salif Keïta refuses

to be fatalist and defeatist and feel pity. “Happiness is

not for tomorrow, it’s not hypothetical, and it begins here and

right now. Let’s fight against violence, selfishness and desperation.

Do no sacrifice to the cult of pessimism. Stand up. Nature gave us extraordinary

gifts. Nothing is done on our continent yet, nothing is lost. Let’s

take advantage from these wonders, cleverly, in our manner, at our rhythm,

like men responsible and proud of their inheritance. Let’s built

something for our children and let’s stop feeling pity for ourselves.

Africa is also the pleasure to be alive, optimism, beauty, elegance,

grace, poetry, sweetness, sun, nature. Let’s be happy to be the

sons of it and let’s struggle together to built our happiness.”

Speeches

translated by the lyrics of “Moffou”, sung in Malinke and

in Bambara, which call up to joy, love and evoke the sweetness and the

benefits of life. This new album is full of colours, energy and emotion.

Dancing and sensual themes, “wild Rumbas” according to their

signatory (Baba, Madan, Moussolou, Koukou) rub shoulders with sweet

songs and ballads.

A lot of

excellent musicians took part in the operation; among them the Guinean

guitar player Djelly Moussa Kouyaté

(whose next album “Sebe Alaye” is awaited impatiently) and

the incredible Kante Manfila (acoustic

guitar), both companion of Salif for so

long. Then, the voice of Cesaria Evora

in Yamore, the accordion of Benoît Urbain,

the harmonica, the marimba and the steel-drums of Arnaud

Devos, the percussion of the crushing Mino

Cinelu, the flutes of David Aubaile

and about traditional instruments: calabashes,

tam tam, congas and djembé

by Mamadou Kone, Adama

Kouyaté, Souleymane Doumbia

and Drissa Bakayoko, the lutes of Jean-Louis

Solans and Mehdi Haddad (Ekova),

les n'goni (small guitars)

of Sayon Sissoko and Harouna

Samake. The whole produced by Jean Lamoot

(Noir Désir, Alain Bashung, Brigitte Fontaine, Mano Solo…).

Wonderful

casting for an album of dream. |

"Le

bonheur n'est pas pour demain, il n'est pas hypothétique, il

commence ici et maintenant. Ne nous laissons pas dominer par la violence,

l'égoïsme, le désespoir. Ne sacrifions pas au culte

du pessimisme. Relevons-nous. La nature nous adonné des cadeaux

extraordinaires. Rien n'est encore joué pour notre continent,

rien n'est encore perdu. Profitons enfin de ses merveilles. Intelligemment,

à notre façon, à notre rythme, en hommes responsables

et fiers de leur héritage. Bâtissons la terre de nos enfants

et arrêtons de nous apitoyer sur nous-mêmes. L'afrique,

c'est aussi la joie de vivren l'optimisme, la beauté, l'élégance,

la grâce, la poésie, la douceur, le soleil, la nature.

Soyons heureux d'en être les fils et luttons ensemble pour construire

notre bonheur. "

"Le

bonheur n'est pas pour demain, il n'est pas hypothétique, il

commence ici et maintenant. Ne nous laissons pas dominer par la violence,

l'égoïsme, le désespoir. Ne sacrifions pas au culte

du pessimisme. Relevons-nous. La nature nous adonné des cadeaux

extraordinaires. Rien n'est encore joué pour notre continent,

rien n'est encore perdu. Profitons enfin de ses merveilles. Intelligemment,

à notre façon, à notre rythme, en hommes responsables

et fiers de leur héritage. Bâtissons la terre de nos enfants

et arrêtons de nous apitoyer sur nous-mêmes. L'afrique,

c'est aussi la joie de vivren l'optimisme, la beauté, l'élégance,

la grâce, la poésie, la douceur, le soleil, la nature.

Soyons heureux d'en être les fils et luttons ensemble pour construire

notre bonheur. " Peut-être

bien le sommet d'une carrière qui commence trente-quatre ans

plus tôt, en 1968, lorsque Salif,

20 piges et des poussières, quitte les rives du fleuve Niger,

les champs et le domicile familiaux pour tenter sa chance dans la capitale,

Bamako. Plutôt qu'un départ : une fuite, une rupture. Parce

que l'enfance et l'adolescence de Salifou Keïta,

venu au monde le 25 août 1949 dans le village de Djoliba (c'est

le premier nom du Niger), au cœur du Mali, n'ont pas été

une véritable partie de plaisir.

Peut-être

bien le sommet d'une carrière qui commence trente-quatre ans

plus tôt, en 1968, lorsque Salif,

20 piges et des poussières, quitte les rives du fleuve Niger,

les champs et le domicile familiaux pour tenter sa chance dans la capitale,

Bamako. Plutôt qu'un départ : une fuite, une rupture. Parce

que l'enfance et l'adolescence de Salifou Keïta,

venu au monde le 25 août 1949 dans le village de Djoliba (c'est

le premier nom du Niger), au cœur du Mali, n'ont pas été

une véritable partie de plaisir. Bamako,

fin des années soixante. La voix de Salif

Keïta, petit à petit, séduit les musiciens

de la métropole. A commencer par le saxophoniste Tidiane

Koné, leader du

Bamako,

fin des années soixante. La voix de Salif

Keïta, petit à petit, séduit les musiciens

de la métropole. A commencer par le saxophoniste Tidiane

Koné, leader du  A

partir de 1997, Salif Keïta retourne

de plus en plus fréquemment au Mali.

A

partir de 1997, Salif Keïta retourne

de plus en plus fréquemment au Mali.